Table of Contents and Abstracts

Chapter 1: Archaeological Evidence in Question: Working between the Horns of the Dilemma

Chapter 2: Archaeological Fieldwork: Scaffolding in Practice

Chapter 3: Working With Old Evidence

Chapter 4: External Resources: Archaeology as a Trading Zone

Chapter 5: Conclusions: Reflexivity Made Concrete

Introduction: The Paradox of Material Reasoning

Ozymandius, King of Kings (Shelley 1819)

Ozymandius, King of Kings (Shelley 1819)Discovery narratives illustrate the intransigence of material evidence: its capacity to bear witness to cultural worlds we had never imagined. But such accounts of ‘confrontation with the past’ misrecognize the complexity of the inferential process by which material traces are identified and interpreted as evidence. Archaeological evidence is an interpretive construct, mediated by technical and conceptual, social and institutional scaffolding; its meaning and import is always contingent on the evolving resources brought to bear in its ‘capture’. And yet, it routinely subverts our efforts to assimilate it to seemingly plausible narratives about the past. This is the paradox of material evidence. In this chapter we introduce the case studies we will analyse: examples of best practice, instructive failures, and examples of mixed success. We offer, on this basis, an account of how archaeologists mobilize the capacity of material evidence to constrain, challenge, and expand our understanding of the cultural past.

Keywords: archaeological practice, discovery narratives, epistemic virtues, evidential constraints, inferential scaffolding, interpretation, material evidence, multiple lines of evidence, objectivity, paradox, pragmatism

Chapter 1: Archaeological Evidence in Question: Working between the Horns of the Dilemma

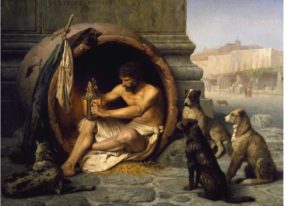

Crisis debates about the nature, scope and limits of archaeological knowledge follow a familiar pattern; cautious pessimism provokes an optimism born of frustration with self-imposed limitations, which in turn generates sceptical critique that calls into question the viability of the enterprise as a whole. A persistent worry that drives this debate was dubbed the ‘Diogenes’ problem in the 1950s: archaeologists might find Diogenes’ famous tub in the town square of Athens, but what could they learn from that about his influence as a Cynic and Stoic?

We find that what drives this polarizing dynamic is an implicit assumption that ideals of deductive certainty and ‘aperspectival’ objectivity must be met for archaeological claims to count as knowledge; if they are not, all that remains is speculation. We trace the history of these debates and argue that they obscure a great many options that lie between the horns of this putative dilemma. Drawing on Toulmin’s analysis of The Uses of Argument (1958) and recent accounts of ‘material inference’ and pragmatism in evidential reasoning (Norotn 2003, Reiss 2015), we reframe these archaeological debates in terms of three pivotal insights. First, the action in building evidential claims is largely ‘off stage’; it is a matter of establishing warrants for the inferences by which primary data are interpreted as evidence. Second, there are no ‘silver bullets’; the strength of evidential arguments depends not on identifying self-warranting empirical foundations but on mobilizing multiple lines of evidence. Finally, evidential reasoning is an extended bootstrapping process of iteratively building and refining tentative foundations for inquiry.

Keywords: aperspectival objectivity, bootstrapping, constructivism, crisis debates, deductive certainty, dilemma, epistemic iteration, evidential reasoning, foundationalism, inferential warrants, inductive inference, material inference, pragmatic theory of evidence, New Archaeology, Processualism, Post-processualism, scaffolding

Chapter 2: Archaeological Fieldwork: Scaffolding in Practice

Discovery narratives illustrate the intransigence of material evidence: its capacity to bear witness to cultural worlds we had never imagined. But such accounts of ‘confrontation with the past’ misrecognize the complexity of the inferential process by which material traces are identified and interpreted as evidence. Archaeological evidence is an interpretive construct, mediated by technical and conceptual, social and institutional scaffolding; its meaning and import is always contingent on the evolving resources brought to bear in its ‘capture’. And yet, it routinely subverts our efforts to assimilate it to seemingly plausible narratives about the past. This is the paradox of material evidence. In this chapter we introduce the case studies we will analyse: examples of best practice, instructive failures, and examples of mixed success. We offer, on this basis, an account of how archaeologists mobilize the capacity of material evidence to constrain, challenge, and expand our understanding of the cultural past.

Keywords: archaeological practice, discovery narratives, epistemic virtues, evidential constraints, inferential scaffolding, interpretation, material evidence, multiple lines of evidence, objectivity, paradox, pragmatism

Chapter 3: Working With Old Evidence

How do archaeologists press ‘legacy data’ into service, sometimes addressing questions that could not even be conceived when they were originally recovered? If evidential claims are the provisional conclusions of Toulmin-style practical arguments (1958) then archaeological uses of old data can be understood as strategies that recover and critically appraise each element of the arguments by which legacy data were originally configured as evidence: the anchoring factual claims, the mediating warrants and their backing, qualifications of and rebuttals to the conclusions drawn. We discuss three strategies for mobilizing legacy data that are informed by this analysis: the secondary retrieval of data through source criticism and re-analysis of primary data; recontextualisation that turns on introducing new interpretive scaffolding (e.g., expanded archaeological comparanda; reframed ethno-historic analogues; innovative strategies of physical dating); and experimental modelling as a means of generating new data. Case studies drawn from research on Hopewell and Mississippian mound sites in the central United States illustrate the first two strategies, and all three are at work in Clarke’s 1972 re-analysis of the Iron Age site at Glastonbury in southwest England. Together these cases reinforce the need to treat scaffolding as provisional and continuously open to reconfiguration.

Keywords: bootstrapping, conjunctives, Eminent mound sites, experimental modelling, Glastonbury Iron Age village, Hopewell culture, inferential scaffolding, interpretive warrants, legacy data, Mississippian culture, old evidence, primary data, recontextualization, secondary data, secondary retrieval, source criticism

Chapter 4: External Resources: Archaeology as a Trading Zone

Given the complexity of the cultural past and the challenges of using material traces to study it, archaeologists must recruit background knowledge and technical skills from enormously diverse fields; no one domain-specific set of resources can provide the range of warrants required to build and assess the evidential claims on which archaeologists rely. This means that in many respects archaeology functions as a ‘trading zone’ (Galison 2010); its success depends on cultivating sufficient cross-field ‘interactional’ expertise (Collins and Evans 2007) to ensure that external resources are effectively calibrated to archaeological purposes.

We consider three cases that illustrate a recurrent life cycle in the reception and integration of technical, scientific imports: the multiple revolutions through which radiocarbon dating has matured; the contentious (UK) history of lead isotope analysis in provenance studies of Bronze Age metals; and the use of stable isotope analysis to infer population mobility in the late Roman Empire. Analysis of these cases throws into relief the central role of ‘robustness’ reasoning in archaeology by which multiple lines of evidence reinforce and constrain one another; we identify a set of conditions that make for productive rather than spurious appeals to the convergence of distinct lines of evidence. It also provides a basis for specifying more closely the social-cognitive norms of community practice that constitute a procedural conception of objectivity (Longino 2002).

Keywords: background knowledge, calibration, inferential scaffolding, interactional expertise, lead isotope analysis (LIA), multiple lines of evidence, procedural objectivity, radiocarbon dating, radiocarbon revolutions, robustness reasoning, trading zones, Roman diaspora, triangulation

Chapter 5: Conclusions: Reflexivity Made Concrete

In response to longstanding, polarized debates about archaeological evidence we argue for shifting the focus of attention way from unattainable epistemic ideals of deductive certainty and aperspectival objectivity to a range of more pragmatic epistemic virtues. Drawing together the threads of discussion in previous chapters we expand on four central themes: how the paradox of interpretation continues to configure archaeological thinking about evidence even though the ‘theory wars’ have largely dissipated; a pragmatic approach that opens up when the terms of this paradox are rejected; the reconceptualization of objectivity we propose; and an account of the role of situated knowledge in concretely grounding reflexivity.

Central to this shift in perspective is an appreciation that the credibility of archaeological claims depends upon mobilizing as many different types of epistemic resource as possible. This extends beyond the disciplinary expertise necessary to appraise a range of different types of evidential claims in technical terms. It includes, as well, the resources afforded by the situated knowledge of those who are insider-outsiders to archaeology whose critical distance puts them in a position to recognize the limitations of entrenched conventions of archaeological practice and envision possibilities they obscure.

Keywords: critical distance, deductive certainty, epistemic virtues, objectivity (‘aperspectival’, procedural), paradox of interpretation, situated knowledge thesis, reflexivity, transformative critique